Aerial view of I-95 under construction in Miami,1960. Aerial view of I-95 under construction in Miami,1960. |

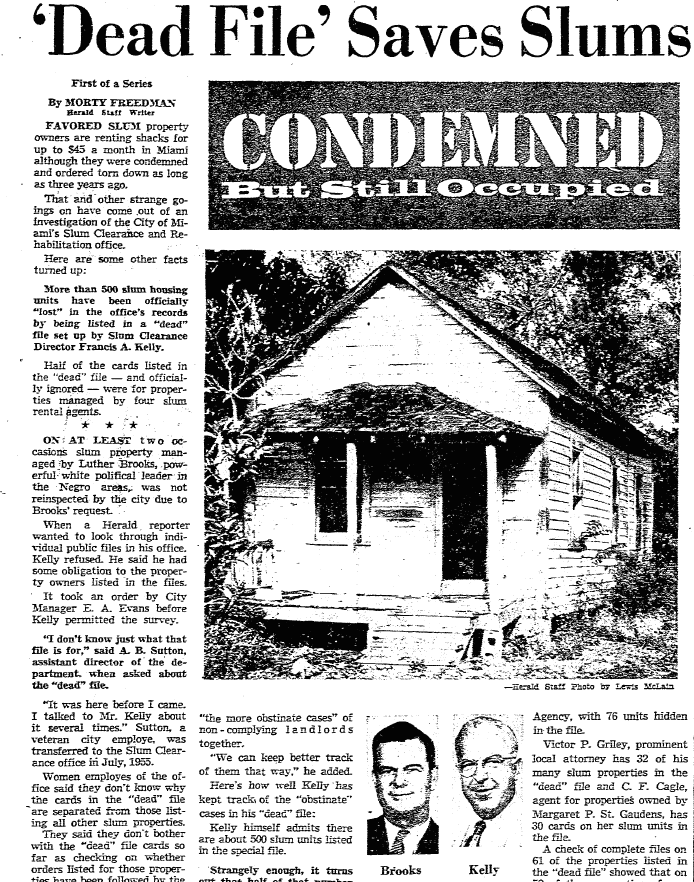

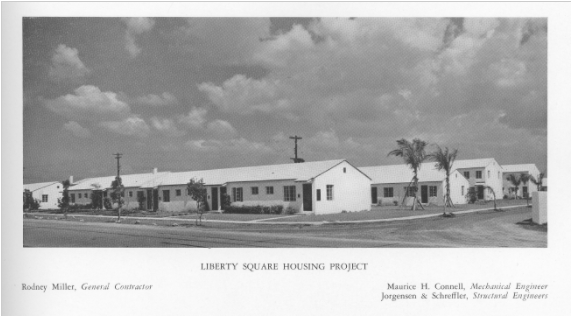

In 1956, Congress passed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, also known as the Interstate and Defense Highway Act. This Act, which authorized funding for an interstate highway network to link major metropolitan areas, had a profound impact on the nation's residential patterns and the built environment. That same year, Florida planning officials acquired federal funds to begin constructing high-speed, urban expressways within the state's 1,160-mile interstate network. During this time, the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, the Urban Land Institute, and state highway officials, among others, promoted using federal highway construction to clear blighted urban neighborhoods and recapture valuable central-city land. Between the late 1950s and early 1970s, massive highway construction significantly increased suburban development in the U.S. while also leading to the destruction of long established, mostly poor and minority neighborhoods in central cities. In 1956, the Florida State Road Department created plans that routed Interstate 95 (I-95) through central portions of Overtown. To better allow for the westward expansion of the Central Business District, state transportation planners rejected an alternative route, proposed by the City of Miami, that effectively preserved residential areas like Overtown by using a vacant industrial corridor for the downtown expressway. The state plan was adopted by the county commission and endorsed by local media, business groups, and various public officials. The construction of the north-south expressway in Miami-Dade County ran roughly from 1957 to 1968. |

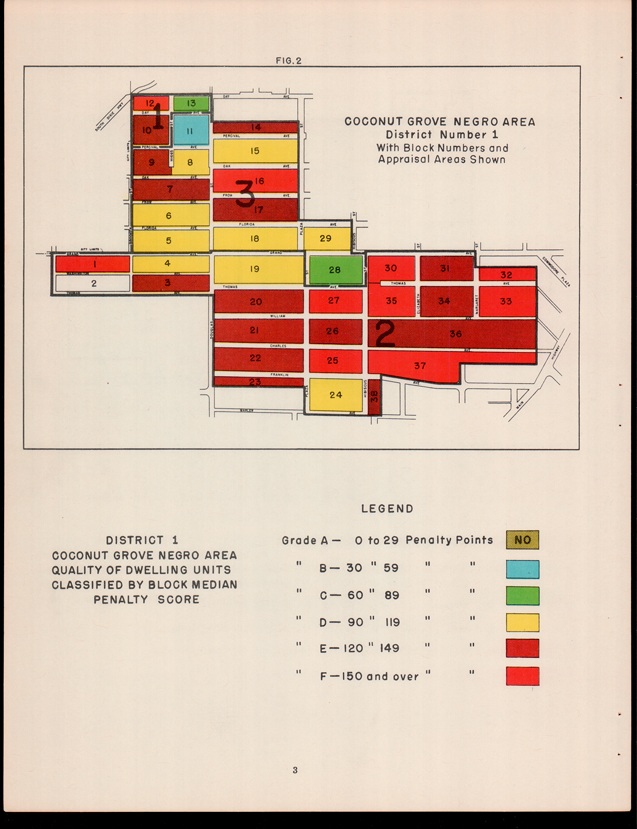

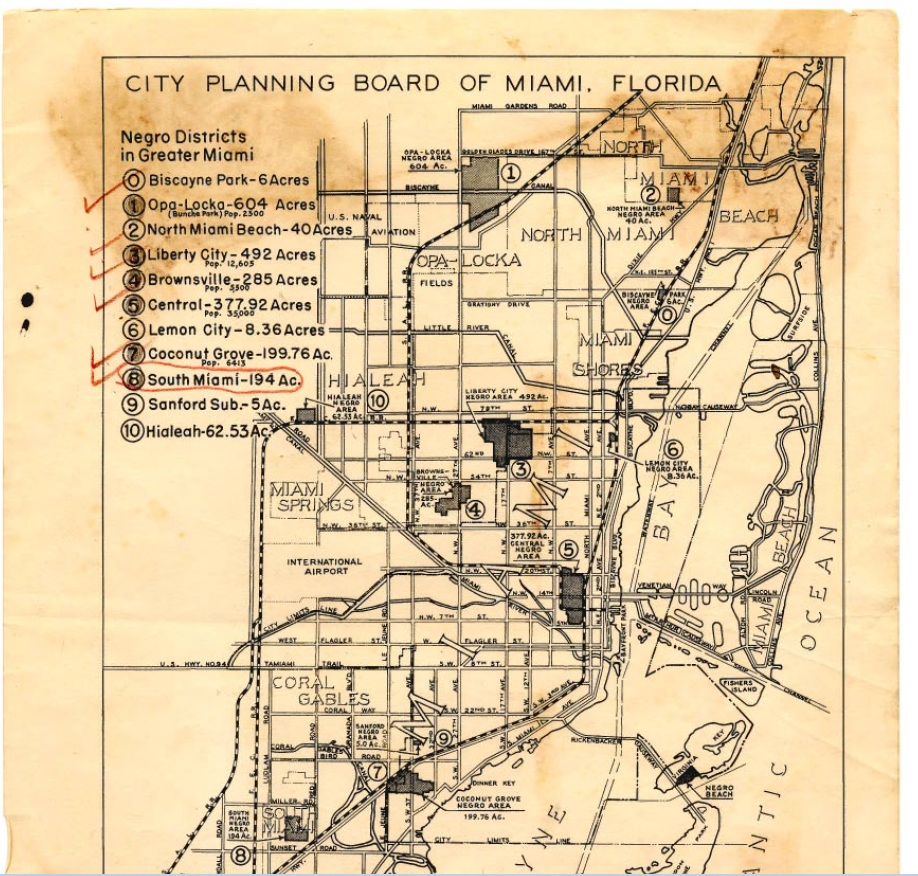

Map of Miami, 1951. "Negro Housing in the Miami Area: Effects of the Postwar Boom."

Map of Miami, 1951. "Negro Housing in the Miami Area: Effects of the Postwar Boom."

Aerial view of I-95 under construction in Miami,1960.

Aerial view of I-95 under construction in Miami,1960.